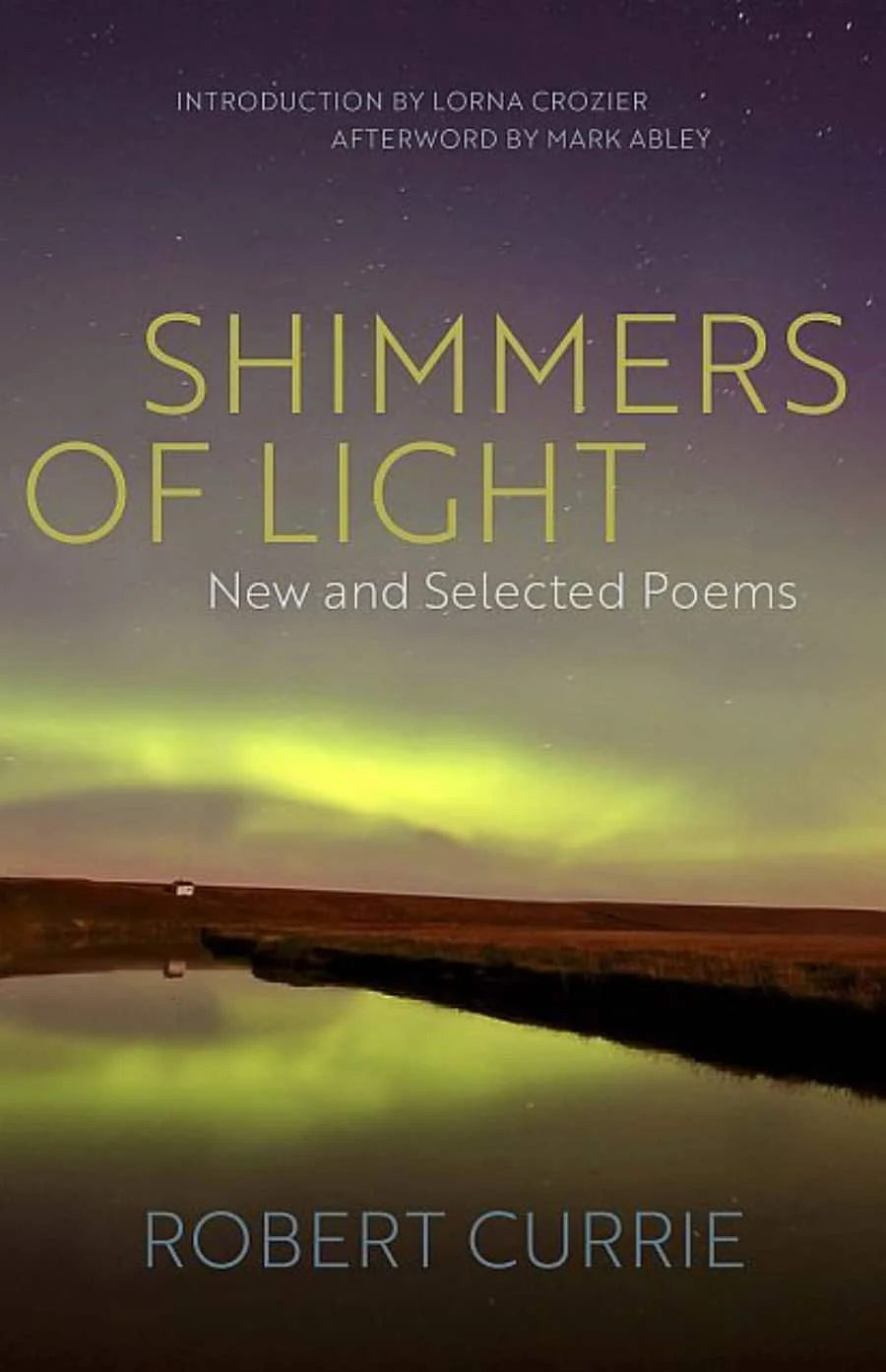

Book: Shimmers of Light: New and Selected Poems

by Robert Currie

Published by Thistledown Press

Review by Shelley A. Leedahl

$24.95 ISBN 978-1-77187-218-8

Multi-genre Moose Jaw writer Robert Currie has been an integral contributor to the Saskatchewan literary scene for as far back as I can remember, and I’ve been reading – and enjoying – his poetry and stories across the decades. Currie’s also worked hard behind the scenes as an educator, Saskatchewan Writers’ Guild board member, and founding board member of the Saskatchewan Festival of Words. He’s also headed the Saskatchewan Writers’ Guild. In short, Currie’s earned his Saskatchewan Lieutenant Governor’s Award for Lifetime Achievement in the Arts.

I’m so pleased that Thistledown Press has released a “Best Of” collection of Currie’s poems. Shimmers of Light: New and Selected Poems is an attractive highlight reel that begins with a glowing essay by poetry veteran Lorna Crozier. She lauds Currie for position[ing] his poems in the local” and “find[ing] a way to rhapsodize the prairies without ignoring its starkness, its closeness to elemental things, and the long, long months of cold.”

Nine sections are dedicated to previous poetry collections (including chapbooks), and New Poems – what I’m especially interested in - begin on page 211 of this novel-sized book. In the new work, Currie continues to mine the rich territory of his childhood and adolescence in Moose Jaw. There are family and sporting memories, including a recollection of racism against a ballplayer in his poem “The Old Ball Game,” and many of the poems make mention of the music that impacted the poet, ie: The Gaylords, Pat Boone, Gene Autry, Elvis Presley, and Johnny Cash.

Currie makes poetry of his first job as a teen: he worked at a feed lot “forcing cattle into the shoot, a needle jabbed into their haunches/while [he] attacked those with horns, sliding a two-by-four/over their necks to hold them, then straining at the/dehorning tool, horns lopped off, steers bawling.”

These mostly nostalgic poems recount scenes of visceral gore and also frequent tenderness. I smiled at the thought of the kids in “Back Then” who raided gardens, yes, but they did this “with care and predetermined rules/two carrots each, always from different rows.” I could see Currie as a tree-climbing child, hands “sticky with sap” while he watched “the whole world turn below.”

People do things in these variously-styled poems. They walk, rake, play sports, read, watch movies, “dance on the band of broken pavement” beside the highway and “[ache] with love, honour friendships, and, in the pieces from the powerful “Klondike Fever” section, they “go blind with staring,” because “Everywhere on the glacier/snow burns in the sun.”

In poet Mark Abley’s Afterword, he discusses Currie’s poetics and how Currie often “begins with an apparently straightforward memory and turns it into something unexpected, almost magical.” I agree.

When I’d reached the book’s end I flipped to the first poem again, “Poet’s Walk,” and read: “bright as blood upon the brambles/as the blackness shoulders in.” Even in his earliest work, I see this poet was doing a kind of singing. We need more singing. And the world could use more Bob Curries.

THIS BOOK IS AVAILABLE AT YOUR LOCAL BOOKSTORE OR FROM THE SASKATCHEWAN PUBLISHERS GROUP WWW.SKBOOKS.COM